Lad Tobin

Sorting Things Out

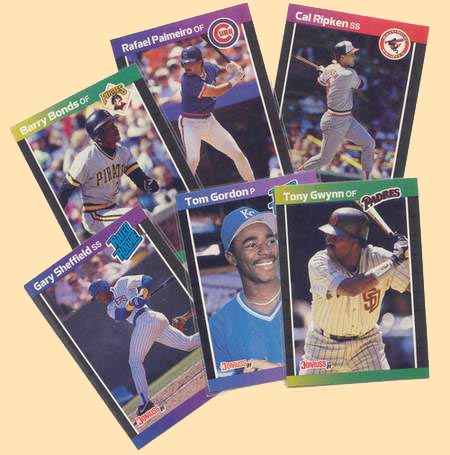

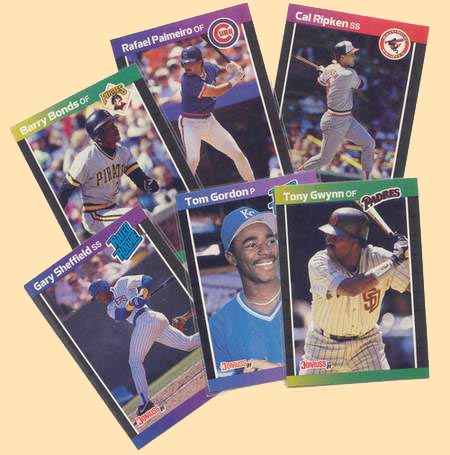

Iím trying to think of a way to make this all sound normal but I know

it wonít be easy: the image of a middle-aged man sitting alone for hours

on his bedroom floor sorting his childhood baseball card collection

into dozens and dozens of neatly stacked piles is just bound to raise

certain questions. The fact that it has been several years since I last

pulled out my cards from the box I keep under my side of the bed might

suggest that this is really not quite as weird as it looks. But the very

fact that I keep these cards in a box under my side of the bed might

mean itís even weirder.

I canít remember buying my first packs of baseball cards Ė it was

sometime in the late Ď50s -- but I can remember the overwhelming,

sickeningly sweet smell of the enclosed stick of chewing gum that would hit you

as soon as soon as you peeled back the waxy wrapping (because that

fluorescently pink rectangle of gum was as thin and brittle as a credit

card, I was never tempted to pop it in my mouth; I would have soon chewed

the cards). I do remember that I was immediately drawn to the look of

the cards (which, given the bright colors, compelling graphic designs,

and blocky, upper-case fonts makes perfect sense to me now). And I

remember that, right from the beginning, I loved the feel of the cards in my

hands, the way you could shuffle them, sort them into piles, or just

hold them, like prayer beads, while you went about your business.

Of course, since I was only five or six when I started collecting, my

business, especially in the summer, wasnít all that pressing. I just had

to find activities to fill up my day and re-sorting my baseball cards

was always near the top of my list. By the time I was seven, I was also

passionately committed to watching baseball on TV, listening to the

un-televised games on the radio, playing little league or pick-up games in

the neighborhood, or staging marathon fantasy major league baseball

games which involved throwing a tennis ball against our garage door or

basement wall and keeping a meticulous mental log of every strike, ball,

hit, run, inning, and result. But as much as I loved the competition and

physical activity of actually playing baseball, I always preferred Ė

and Iím still a little sheepish about admitting this, even to myself --

the time I spent thinking about the games I invented, fantasizing about

games that could be played, replaying games I saw years before.

Iím sheepish about this inner baseball life because Iíve always

worried it was just one of the indications that at some point I had crossed

the line from a normal, well-adjusted person with a passionate interest

in sports to a misanthropic guy with a weird fantasy life: in other

words, I knew it wasnít unusual to watch baseball games, read the sports

pages and box scores, and discuss the games with other fans. I knew that

more diehard but still relatively normal fans might memorize a few

statistics, collect some autographs, maybe even fly down to Florida to

follow their team in spring training. But spending an afternoon trying to

figure out what would happen if an all-star team from 1959 played an

all-star team from 1969 was probably further down the list of normal fan

activities. And spending your entire morning sorting your entire card

collection according to the playersí birthdays was probably off the list

altogether.

Of course, given the proliferation of fantasy sports games and leagues

which now occupy the time and passions of an increasingly and

disturbingly large number of men in the 18-45 demographic, this privileging of

games about the game rather than the game itself no longer seems quite

so strange. In fact, today itís not at all unusual to find fans that are

involved in an office or dorm or Internet league in which they all

pretend to be general managers of pro teams whose progress they then chart

and bet on and compare to other fantasy teams. But my virtual baseball

life preceded this phenomena by a few decades and, even by todayís

fantasy standards, it still seems that any kid who would turn down an

invitation to join a pick-up game at the park in order to sort thousands of

cards which he would then mix back together several hours later must

be, well, a little weird.

Or even downright pathological. The fact that I still keep the cards

under my bed, the fact that I am waxing nostalgic about the smell and

feel of the cards in my hands, the fact that I valued time spent alone

staring at 3Ē by 2Ē pictures of professional baseball players as much as

time spent actually playing the game with actual humans -- all this

seems to indicate a full-blown fetish of some sort. Certainly part of the

pleasure, as Iíve just confessed, was the tactile, sensual delight of

handling the cards and staring at the pictures. And so it wouldnít take a

clinical psychologist to figure out that the cards must have held for

me, especially as a pre-teen, some sort of pornographic, possibly

homoerotic, element, an idea supported by the fact that I looked at those

pictures so long and hard that I could identify every single player in my

collection, whether the name was visible or not (in fact, I realized at

one point that I could recognize every player even if most of the

card was covered, exposing only a mouth or eye or eyebrow, a skill my

mother told me once would come in handy only if I happened to walk past

one of those players while he was wearing an elaborate disguise). I

suppose the pornography theory is supported, too, by the fact that when,

as a teenager, I discovered and collected some magazines which had naked

pictures of women, I stashed that collection under my bed, too.

All collectors of essentially useless objects open ourselves up to

teasing and armchair diagnoses. Maybe the impulse to search for, acquire,

collate, and horde anything -- whether itís baseball cards, vinyl

records, fancy shoes, war memorabilia, action figures, spoons from around the

world, Barbies, or X-rated videos Ė is always definitive evidence of

arrested development, sexual sublimation, anal retentiveness, obsessive

compulsion, castration anxiety or penis envy; call it what you will, Iíd

still argue that the time Iíve spent playing with baseball cards was

more therapeutic than pathological, more worthwhile than worthless.

In fact, it was through studying my collection that I came to gain

almost all of the skills I needed to get me through school, if not through

life. My mother claims in the summer before I started kindergarten that

I taught myself to read by matching up the letters on the cards to the

pictures of the players I knew by sight. Iím certain that I owe my

basic number sense and math skills to endless hours adding up and dividing

the statistics listed on the back of the cards; to this day, I still

think in percentages, averages, and probabilities. And there were all

sorts of smaller, more particular lessons I got from studying those cards.

For one thing, by sorting the cards into home states, I learned

geography. I not only knew the names of thousands of cities and towns in all

50 US states, I had very early on a working familiarity with place names

in the islands in the Caribbean and the countries of Central America. I

knew how to match up the spelling with pronunciation of Spanish

names (that, say, the Ls in Mike Cuellar and the J in Jesus Alou were

silent or that the Is in Louis Tiant were pronounced as long Es). I

even learned how to read and write cursive since in certain years the

cards contained the playerís autograph across the picture.

As valuable as this information was, it pales next to the spatial or

architectural education I gained from the time managing my collection.

Iím not certain I was ever consciously aware that all that sorting was

seeping into the way I viewed every new word or number or text or idea I

encountered but as I reached high school and then college, I began to

realize that my whole learning style had been shaped by the time I spent

mixing and matching my cards. Whether I was organizing a composition in

an English class or memorizing a long list of information in a history

or science class, I found that the process felt uncannily familiar. It

was as if I had already established networks of connected grooves,

categories, taxonomies, and family trees; I just had to plug in the new

information.

Iím convinced that I was able to have a career as a writer and writing

teacher because I developed the ability early on to read a rough draft

-- my own or someone elseís -- and quickly see a variety of ways that the

ideas could be linked, juxtaposed, re-ordered; that is, I could quickly

see -- and take enormous pleasure from -- the great variety of ways

that the same ideas, facts, or statistics could be sorted into coherent

and colorful piles. Again, I certainly wasnít spending all of those hours

and years sorting and re-sorting my ever-growing box of hundreds and

then thousands of cards into piles by teams, then year of birth, then

height and weight, then home state, in order to gain practical, useable

skills, but what I know about organization, spatial relations, and

diligence was first established in my work and play with those cards.

All of this may begin to explain why I first put a box of cards under

my bed when was I was seven but Iím not sure it really gets at why I

keep it there now that Iíve passed 50. I suppose part of it is that, like

Joan Didion has said about the journals she kept, my cards keep me

connected to myself or to the self I was at particular times in my life.

What comes back to me most strongly each time I glance at my cards is an

odd mix of melancholy and gratitude -- melancholy because I think I

usually immersed myself in sorting when I was feeling lonely, lost, or

anxious and gratitude because the act of organizing and ordering the cards

somehow distracted and even soothed me in a way that made me feel less

lonely, lost, and anxious. And, while as an adult Iíve found other ways

to deal with anxiety and depression, there is some part of me that

still views the cards as a security blanket.

I suppose I also keep the cards because Iím not sure what Iíd do with

them otherwise. While I assume that some of them are fairly valuable

(Iíve got dozens of cards of Hall of Fame players such as Mickey Mantle,

Willie Mays, Sandy Koufax, and Roberto Clemente), Iíve never been

tempted to sell them. In fact, Iíve even resisted finding out how much they

are worth for fear of finding out either that they are worth so much

money that Iíd feel like a fool for not selling them or that they would

have been worth that much money if only I had kept them for all these

years under protective plastic rather than handling and sorting them

several thousand times. In any case, Iíd think Iíd feel uncomfortable or

guilty seeing something that possesses so much sentimental and

psychological weight for me reduced to dollars and cents.

Which brings me back to why Iím sitting on my bedroom floor surrounded

by piles of cards sorted this time by the playersí birth dates. Itís

taken me almost an hour to find a player with my birth date -- January 6 --

which, given the fact that Iíve probably sorted over 500 cards strikes

me as a probability-defying phenomena (and, in fact, a quick email

query to and response from a mathematician friend of my wife reveals that

the odds of finding a ďbirthday twinĒ rise above 50% after only 253 cards).

And Iím struck, too, by the fact that the first player I find with my

birthday, Joe Lovitto of the 1972 Texas Rangers, is such an obscure card

and player that I donít even remember him. Reading through his meager

stats -- those years in the minors, those years when he barely got off

the bench and into the game -- I find myself feeling a little sorry for

old Joe and, Iím embarrassed to admit, for myself. After all this time,

all this searching, this is all there is? While it may have been

too much to hope that Iíd discover that I share a birthday with stars

like Mickey Mantle or Willie Mays, it still sets me back for a minute

to finally find my doppleganger and to see that he -- and I? -- are just

bench warmers.

I know this is ridiculous but this strikes me as sobering news -- and

makes me stop short. In fact, Iím tempted to throw all the cards back

into the box, push the box back under the bed, and find something real to

do with my day. For some reason, though, the possibility -- no, the

mathematical probability (or is it near-certainty?) -- that Iíll find many

other January 6-ers in my collection keeps me going. But after scanning

the back of the very next card -- Larry Doby; Born: 12/13/24 Ė I

hesitate again. I remember Doby not only because he was star player during the

period when I first started following baseball in the late Ď50s but

also because he was the second African American player in the Major

Leagues (Jackie Robinson, of course, was the first black player, breaking the

color barrier in 1947, just eleven weeks before Doby did it). I

remember reading that Doby was always frustrated that, even though he had to

endure all of the same bigotry and prejudice that Robinson went

through, he got little attention since the media and fans had already

tired of the story. Amazingly enough, many years later, Doby become the

second African American manager in the major leagues and so again his

story was overshadowed.

Dobyís hometown is listed on his card as Paterson, NJ, which makes me

think of William Carlos Williams, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet who, I

knew from my days as a grad student in English, was writing the first

books of his epic poem, "Paterson," at right around the same time that

Larry Doby was breaking baseballís color line. I knew, too, that Williams

also felt overshadowed -- in his case, by T.S Eliot and the other

modernist poets. Were these two residents of Paterson, NJ even aware of each

other? Did they ever meet in 1947 to celebrate their groundbreaking

achievements or to commiserate about the fact that they had not yet

received their just desserts? For a second, I consider the possibility of

developing and marketing poet cards, with color photos or portraits on the

front, stats about publications and awards and maybe a famous quote or

two on the back. I find myself imagining the Robert Frost card, which

could include that famous photo of his reading at Kennedyís Inaugural and, on the back, maybe ďThe woods are lovely dark and deep/But I

have promises to keep,/And miles to go before I sleep,/And miles to go

before I sleep.Ē

Shaking myself, I remember that I also have a long ways to go before I

can quit for the day: I still have many piles of cards spread out on

the floor and, so far, only poor Joe Lovitto in the January 6th slot.

Returning to reality (or at least what passes for reality in my fantasy

life), I carefully place Larry Doby in the sizeable December 13th stack,

reach back into the box, and continue putting my things in order.

©2006 by Lad Tobin