Fred Afflerbach

Bobo, Hank, and Me

My Hank Aaron baseball card is missing and I know who took it -- Bobo. He was here at my house yesterday and we were trading baseball cards; then I went to the bathroom and I heard him say he had to go home. When I came out, Bobo was gone. And so was Hank.

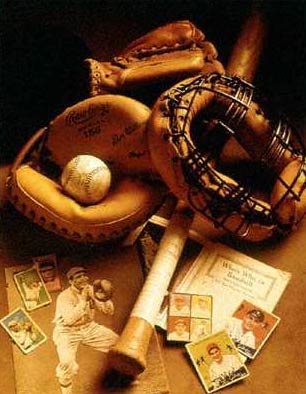

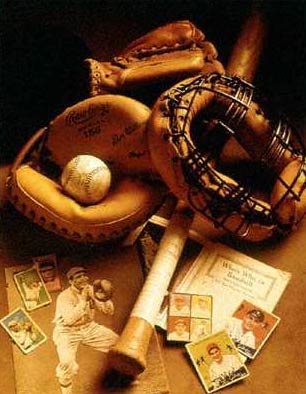

Now you have to know what Hank Aaron means to me to understand why I'm so mad. About two years ago me and my two brothers, Stephen and Kenny, found a bunch of old baseball bats in a steel trash can up at the Little League Field. I thought we had found lost gold. We hammered little finishing nails in the cracks and then taped them up real good with some of Dad's black electrical tape that I had found in the garage. Then I started hitting with this one bat, an Adirondack Special, and I went on a hitting streak and

Coach moved me up to leadoff hitter. We won first place when I knocked in two runs in our last game. And that bat was autographed by Hank Aaron.

That summer I spent all my paper route money on baseball cards, but no Hank Aaron. Finally, I heard about this kid who had a Hank Aaron card. He lives off McCarthy Road. I'm not allowed to ride my bike that far, but I did. If Dad ever finds out, I know he'll take Pepper -- that's my bike -- and I'll be walking for a while. Anyway, I traded this kid my Mickey Mantle card for Hank Aaron. Everybody laughed at me but I told 'em, “Hank's gonna pass up Mantle and Mays in home runs and maybe catch Babe Ruth too.” They all laughed again.

But back to my friend, Bobo, he goes to public school so I didn't see him today. But as soon as Sister Francis let us out I rode Pepper straight to Bobo's house.

Lately, all of us kids have been swiping clothespins off of our mom's clotheslines out in the backyard, and then we pin some old baseball card that we got about a hundred of--like a Bob Uecker--to the wheels of our bikes, and then we blast down the streets and alleys like we're riding motor scooters. So I came roaring up Bobo's driveway with baseball cards flapping in both wheels. His Schwinn was standing up on the front porch, leaning against the kickstand. He had a shiny new chrome handle on the stick shift. I'd seen those chrome shifters at Western Auto and they cost over four dollars! I know Bobo wanted that chrome shifter real bad, that's all he talked about for weeks. I guess he must've begged his dad long enough -- Bobo was good at begging his dad to get what he

wanted. I rang the doorbell. Bobo slid open the front window and pushed his nose against the screen.

“What do you want, Rusty?”

“I want my Hank Aaron card?”

“I ain't got your Hank Aaron.”

“Liar.”

“I ain't got you're stupid Hank Aaron.”

“Liar, liar.”

“Go home, Rusty.”

“Let me in,” I kept knocking. Sweat was pouring down my face.

Bobo's face was smushed flat against the screen and he sounded like he had a clothespin stuck on his nose. “My parents said no one's allowed inside if they're not home.”

“I want to see,” I yelled. “I want to look through your cards.”

“Okay, Okay.” Bobo came out on to the front porch. For just a couple of seconds, when the door was open, I felt cool air rushing out -- I wish we had air conditioning.

We sat on the front porch, in the shade, and Bobo opened up his shoebox.

“Here's all my Braves,” Bobo said. “See.”

I pulled the rubber band off the stack of cards--Joe Torre, Clete Boyer, Eddie Mathews--I looked through 'em all, but no Hank Aaron.

“Told ya, Rusty, I didn't take it.”

“I know you did,” I said. “I went to the bathroom and you snuck out with Hank Aaron, you're always trying to pull something, Bobo, like when you traded Kenny a Check-List for Al Kaline.” I picked up a stack of cards, it was the Washington Senators. “I'm not leaving till I look through every single card you got.”

Then Bobo grabbed the cards out of my hands and before I knew it he slammed the door and locked it. “I ain't got your Hank Aaron,” he yelled.

I stood up and kicked Bobo's shiny bike. It fell over and I saw a beat-up baseball card attached to the back wheel with a clothespin. I squeezed the clothespin and pulled out the card. The front picture was rubbed off so I flipped it over.

“Bobo.” I banged on the front door. “You put my Hank Aaron card in your spokes.” I could hear I Love Lucy on the T.V.-- Lucy and Ricky were arguing. I looked hard at the back of the card -- the bicycle spokes had rubbed off the name but I could read the statistics: 44 home runs for Milwaukee back in 1963, .328 batting average, born in Mobile Alabama on February 5th 1934. It was definitely Hank. Tears and sweat were flowing down my face, I couldn't tell the difference. I started reading and yelling louder--“510 career home runs, 313 lifetime average, bats right, throws right.” But Bobo had turned up the T.V.--he couldn't hear me above Ricky Ricardo arguing in Spanish.

I went through the gate to Bobo's back porch. They had a sliding glass door and I cupped my hands around my eyes and pushed my face against the glass. I couldn't see Bobo, but now there was a Rice Krispies commercial on TV. Those three little guys, Snap, Crackle, and Pop were in color. Bobo had air conditioning and color T.V.

Then Bobo came into the room. “I didn't take Hank,” he yelled through the glass. “Honest, Rusty. You can get another Hank Aaron anyway.”

“No you can't,” I yelled back. “He's even harder to get than Clemente or Frank Howard, everybody knows that.” Suddenly I felt like I did in that game we lost 23 to nothing. I just wanted to go home and hide in my room.

“We're not friends anymore, Bobo,” I said. “You're not my friend.”

“Fine, then get off my porch.”

Then I said something I've never said in my life. And I hope Sister Francis never finds out. I didn't mean to say it, but the words just came out of my mouth, like I was throwing up, three words I wish I could take back -- “I hate you.”

I had lost my best friend and my best baseball card and I just wanted to go home. I went back around to the front porch and there was Bobo's bike. Then that feeling was all over me again, like a bad sunburn, stinging my skin all over. I don't know what happened to me but I just starting kicking Bobo's bike again and again. The shiny chrome knob on his shifter fell off. I stuck it in my pocket and I got on my bike and rode home. Payback.

When I got home two bundles of evening papers were waiting on the front porch. I started rolling the papers and placing green rubber bands around each one. I saw the same headline 49 times -- “Martin Luther King Jr. Assassinated in Memphis.” I'd never heard of Martin Luther King Jr., but I'd never heard of Robert Kennedy either until he was killed. And I still remember back in first grade, when I came home from school, and Mom was crying in front of the T.V. She sat there for hours while the reporters talked about President Kennedy and a man, Oswald, I think that was his name.

As I was riding around throwing my papers I wondered why these people keep getting shot. And the more I thought about it the less I cared about Bobo and the baseball card. I would never be his friend again, but I didn't hate him either. And I wished I could take those words back.

After throwing all my papers I rode over to the dirt lot we call the scramble tracks. If I'm not playing baseball, then I'm working on my stunts and jumps here at the scramble tracks. All of us kids in the neighborhood got together and built some ramps out of scrap wood we found when some men were building a new house down the block. So far I'm still the best--I can get Pepper up in the air higher and longer than anybody, even kids older than me, like seventh and eighth graders.

The next day, while I was rolling my afternoon papers, I peeked at the sports page. Today was opening day and I just knew Hank Aaron and the Braves would win

it all this year. But opening day was cancelled in Los Angeles and Baltimore, and Atlanta too. Because of Martin Luther King Jr. being killed, the negroes were rioting and burning. It felt like the whole world was falling apart.

The baseball season finally started, school let out for the summer, and it looked like the sun was gonna keep on coming up every morning no matter what. Then later that summer Dad asked if I could find someone to throw my paper route for a week -- we were going to Houston on vacation and he had tickets for a Braves -- Astros game. I nearly exploded through the roof. Hank Aaron? The Astrodome? This was better than beating those rich kids from Lakeside in the All-Star Game.

I begged Mom for an old mop stick and I nailed a big piece of cardboard to it. Then I did some more begging and got Kenny to let me pluck some feathers from his Indian Halloween costume. I used up two boxes of Crayolas, but when I was finished I had me a four-foot-tall GO BRAVES sign with feathers on top.

I've got three sisters and two brothers and we all piled in the station wagon tighter than a bunch of baseball cards in a shoebox. When Dad stops at a rest area us kids rotate from the front seat to the middle and then to the way back. We all hate the way back; it's hot and you have to ride backwards. But I'd ride upside down to get to see Hank Aaron. And Dad said the Astrodome was air-conditioned.

In Houston, Dad checked us in at the Best Western Motel, they've got a pool and an ice machine, but best of all, it's only a couple of blocks from the Astrodome.

I'd never seen anything so beautiful. My little brother, Kenny, looked up and said, “Is this where God lives?” If Sister Francis had heard what Kenny said she probably would've fainted, but the Astrodome really did look like a place where God should live.

Everyone except me jumped straight in the swimming pool. Dad knew what I wanted and he gave me my ticket. With my GO BRAVES sign I walked to the Astrodome and got there early enough to watch batting practice. During the game some people behind me kept yelling at me, they said my sign was blocking their view, so I kept it down except when Hank was at the plate. And Hank went three for four with two doubles and a single. And we won the game six to one -- of course when I say we I mean the Braves.

After the game I waited outside the Braves' bus. I had a pen and a spiral notebook ready and then a bunch of men, all in brown suits, came down the breezeway. Kids were pushing each other trying to get close. I was getting knocked around pretty good. Then I saw Hank.

“Wait till I'm on the bus,” was all He said.

Everybody rushed to the window where Hank was sitting. We were all jumping up and down in front of his window. I couldn't get close. Finally, I untied the feathers on my GO BRAVES sign, threaded the string through a hole in my spiral, and real quick made me a granny knot. Then I lifted my sign over everyone's head. The

spiral dangled from the end of the mop stick right in front of Hank and he reached out and grabbed it like it was a fly ball in right field. I was more nervous than I was at my first confession. Then the bus started to leave. It started real slow and Hank held my spiral out the window and let go but my knot came untied. The spiral fell to the parking lot and the bus drove away.

People were pushing like it was Halloween trick-or-treating and all of the houses were running out of candy. I dropped my sign, and with both arms, shoved my way through the crowd. And there was my spiral next to a flattened out Coca-Cola paper cup. I must've got stepped on about ten, twenty times but I grabbed the spiral and opened it. On the first page was the autograph -- Henry Aaron #44.

Maybe the world wasn't falling apart after all.

Summer was over. It looked like the Braves weren't going to catch the Cardinals or the Dodgers and I would have to wait another year to see Hank in the World Series. After the first day of school, I don't know why, but I went down Bobo's street, maybe I wanted to brag that I got Hank Aaron's autograph, I don't know.

But when I turned the corner there was a giant truck in front of Bobo's house. The front of the truck had license plates from faraway states like Arkansas and Oregon and Mississippi -- states that were just answers to questions on a Geography test to me. Two big smokestacks were pointing towards the sky and the giant chrome bumper, windshield, and headlights were splattered with grasshopper guts, butterfly wings, and squished mosquitoes. Then two men wore gray uniforms, one real short, but with big

muscles that stretched out the sleeves of his shirt, and the other tall and skinny, rolled a dolly with a refrigerator strapped on it out of Bobo's front door and up a ramp into the moving van. I got off my bike and just stood there on the sidewalk in front of Bobo's house.

“Hello, kid.” The tall man was walking back down the ramp toward the house.

“Where is everybody?” Bobo's dad drove a big black Oldsmobile. It wasn't in the driveway.

“Nobody's here. They've already gone to Albuquerque.”

I wasn't sure how far Albuquerque was. But I was sure it was a lot farther than Houston.

“They're moving to Albuquerque?”

“Well, yeah. The lady and the boy are.”

“You mean, Bobo?”

“Yea, Bobo, that's what I heard his mama call him.”

“Where's the dad?”

“I heard he had an accident at work.” The man pulled a red handkerchief out of his back pocket and wiped the sweat from his face. “Terrible thing -- just awful. The boy and the lady are going to live with her parents.” The man folded up the handkerchief and tucked it into his back pocket. “What did you call the boy?”

“Bobo.”

“Were ya'll friends?”

I couldn't talk. I couldn't think either.

“Were ya'll friends, kid?”

“Yea,” I said. “We were friends.”

I climbed on Pepper and rode off. I never saw the boys coming. There were three of 'em and they rode up beside me and tried to push me into the ditch.

“Catholics. Haaaa-Haaaaa. You're a CATHOLIC!”

I'd never seen these kids before. They were bunched up around me pushing me closer to the ditch. I started pedaling faster and faster. Why were they after me?

The biggest kid had long and greasy hair. He kept shaking it back out of his eyes. “Catholic. You're a Catholic”

Then I knew. I still had on my khakis and my St. Joseph's shirt. They were laughing louder and were riding up closer and closer, pushing me up against the ditch. It hadn't rained in a while but the ditch was still muddy and it had a little water standing in the bottom. Then I saw a huge tree trunk spread across the ditch like a bridge for kids. I turned my handlebars and rode Pepper across the tree trunk and over the ditch. I kept pedaling but looked over my shoulder. Two of the kids had stopped, but the big one with the long and greasy hair was riding hard towards the ditch. His bike hit the tree trunk and his front wheel and handlebars jerked sideways and he flew headfirst into the ditch.

I cut through the alley behind Crockett Street and in about five minutes I was safe at home. I dug around the floor of my closet -- there were my baseball cleats, my glove, my church shoes, and a bunch of dirty socks, and then I saw it. The bedroom light was

shining in like a flashlight, and I saw the chrome sparkling. I grabbed it up and stuffed it in my pocket.

I ran outside like I was trying to steal second base. “Don't slam the door,” Kenny yelled from inside the house as I climbed back on Pepper. “Yea, I'm telling,” I heard another voice, probably my little sister, Nancy, she's a natural-born tattletale.

I didn't have time to change out of my school clothes and I wasn't going through any more alleys either. I had to get back to Bobo's before the moving van left. “There he is.” I heard voices behind me. “Let's get him. He's a Catholic.”

I put my head down and leaned over my handlebars. Then I stood up and pushed down on the pedals with all my weight as fast and as hard as I could. I felt the chrome knob rubbing up and down inside my khaki's pocket.

“Catholic. You're a Catholiiic.” Now their voices sounded farther away. I turned the corner to Bobo's street. The men were walking down the ramp out of the moving van and back into the house. I was close enough to see Bobo's bike inside the moving van, lying on top of a stack of boxes.

It felt like I was doing 90 miles an hour when I hit the bottom of the ramp. I went flying into the back of the moving van, and leaning sideways, locked up the back brakes, power sliding up against the stack of boxes. My elbow dragged on the wood floor and I could see it bleeding -- it looked like I'd have a big scab for a while.

I couldn't reach Bobo's bike, it was too high. I could hear the men coming down the sidewalk. I peeked out the back of the moving van. They were coming with a sofa. I

leaned Pepper up against the stack of boxes and climbed up on the banana seat. Then I pulled the chrome knob out of my pocket.

“There's that kid up in the van,” the movers' voices were real close now.

I pushed Bobo's chrome knob onto the shifter. Then I dropped down right on top of my banana seat with my legs spread wide open. That's the most pain I think I've felt since a grounder took a bad hop in practice one day and I had to limp home. At least then I had on a supporter. Mom made sure I wore a supporter.

Me and Pepper flew down the ramp out of the moving van and we shot past the movers carrying the sofa. “Hey, kid, what did you steal?” I heard one man yelling. But by then I was racing around the corner with one hand on my handlebars and the other on my privates.

I took a short cut through an alley, but it was blocked. Old greasy hair was sitting on his stingray with his arms folded across his chest. I rode up slow and stopped right in front of them. Greasy hair's t-shirt and blue jeans were black with mud. He wrinkled up his nose and squinted like he was looking straight into the sun. “You're Catholic,” he sneered.

The two other kids looked scared. They were just, maybe, third or fourth graders. Then the littlest one looked at me. “Where did you learn to ride like that?”

“Catholic School,” I said.

I turned Pepper around and did a figure-eight like I was at the scramble tracks. Then I pulled back on my handlebars and raised Pepper up on her back wheel and rode right through the middle of their roadblock.

“Did you see that?” I heard one kid say as I rode off. Then I heard greasy hair tell him to shut up.

I turned the corner to our block, and Kenny was riding his bike down the sidewalk. His bike was loud, I could hear baseball cards flapping in the spokes of both wheels. I rode past Kenny and smiled and waved. At home I poured a tall glass of ice water and went to my room. My shoebox was open on the bed.

I ran outside, letting the screen door slam hard behind me. I jumped on Pepper

and raced down the block. I rode up beside Kenny, grabbed his handlebars, and made him stop. “Are those my baseball cards in your spokes?” Kenny was scared. “Are they? Kenny?”

“Well, yeah. But, Rusty, I didn't think you'd care. You got a whole box full of 'em.”

I pulled the cards out of the spokes. “You ruined 'em both, Kenny. You owe me a Joe Adcock and a Felipe Alou. You're gonna have to do some serious trading 'cause both these guys are hard to get.”

“Rusty, I'm sorry,” Kenny was almost crying. I was so mad but my little brother crying just made me feel sad instead. “Why? Why, Kenny? Why?”

“Rusty, I'm sorry,” Kenny said again. “But I owe you one more,” Kenny was rubbing his eyes with the back of his fists. “Remember the last time Bobo came over? Back when ya'll were still friends, and ya'll were trading cards? Well, Bobo let me borrow his bike -- I'd never rode a bike that nice before, Rusty, and while you were in the bathroom I grabbed a card off the top stack and I pinned it on Bobo's bike.”

“Off the top of the stack, Kenny?”

“Yeah, Rusty. I'm sorry. I just grabbed the top one. I didn't even look at who it was. Then Bobo said he had to go home and that you'd been in the bathroom forever and he had to have his bike back.”

My stomach felt like the time I crashed at the scramble tracks and the handlebars caught me right in the belly, knocking the wind out of me so I couldn't breathe.

You see, I always kept my baseball cards in alphabetical order.

©2006 by Fred Afflerbach