Lizzie Hannon

The Phoenicians

#1

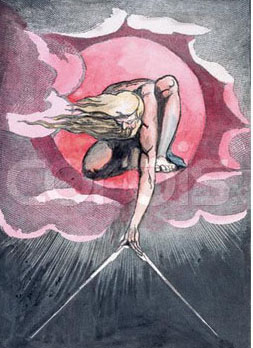

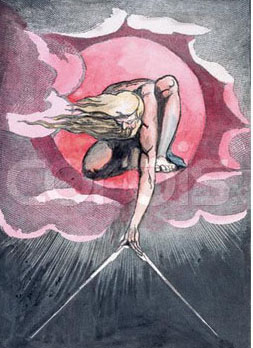

I troll an oily ocean in a small skiff on a black slicker night. I am bobbing between waves of memory and whitecaps of feelings about those memories. I am here to snag from the depths some truth of how my mother survived the corrosive force of time, the sandpaper of anger upon hearts and minds. My mother carried words as life preservers, books as boats to sail out from a day of dying. I cannot see her but sense she lies below. I cast a line into this sea of time, watch it spin from my fingers allowing it to carry me down like Jonah, down to what we imagine will swallow us, down to the pain of the past.

It is your siren song I hear tonight, Mother. With the harvest moon as klieg light, I dare to dive deep into our history, part the water like Moses, and walk the bottom free of fear to the port you fled to after the final storm, using the Polar Star as taught by your tribe. At last this evening I am ready to sail back to find you, back to the land of Canaan -- where people first took papyrus in hand and began the sounding of stories, back to the valiant and doomed passage of the Phoenicians.

#2

My parents slept in the living room on a pull out couch. In the room with that couch and an easy chair for my father was a small bookshelf, the kind where you raise or lower pegs to make a stall tall or wide enough for each row of books. On the bottom left were peppermint pink and mint julep green books for boys and girls, Swiss Family Robinson, Little Women, The Canterbury Tales. On the far right side of this shelf the pegs were set high, creating a lofty roof to hold the heavy hardbound museum books my mother favored. It was familiar as peanut butter to swing home from school, into our shoebox kitchen, to find her at the far end of the plaid sofa under the soft light of a white porcelain lamp, eyes following the curve of print. She could more easily be in Rome or Venice than a small dairy town. What stays with me to this day, the page which memory falls open to in this moment, holds a heavy book with gold edging. My mother has propped the oversized tome in her lap, resting its weight against thin thighs, reclining the spine so pages sigh open, breathing with my mother, as she caught a familiar current, sailing far from family and fate to the time when a colony of olive-skinned people settled land at the edge of the Mediterranean, vowing if need be, somehow, some way, they would ride out upon the water -- a band of phenomenal sailors known as Phoenicians.

There was nothing I could fish from the small tide pool of my day that could compare to the marvelous adventure unfolding before my mother's eyes, guided to a history so ancient no written records remain, only the pieced together story from shards and relics of what once was an empire. And it was mystery working from behind the scrim of conscious thought that joined her hands to this book, that bent close for only her ears to hear, "This is your world, Beatrice Marie Hawley Hannon, you have conquered lands, discovered purple dye the color of kings, and you have taken papyrus in hand and with your own mind, with your own mind, begun the alchemic process which today we know as the Greek alphabet, but you, your tribe gave them letters, this book is your heritage, their story is your story, never mind this four-corner house, come with me today, for the sea is calm and you, Beatrice, are called to journey beyond the facts of life, back to mystery, back to what will save you, what will save us all from what lies ahead -- the power of imagination."

#3

In the gray-shingled house where I grew up we had one closet, a coal furnace, two bedrooms for the six of us, and hope. Hope came in the guise of the stories we read about how other people, real or imagined, persevered. All of us counted on characters in books to provide a road map for how things could be outside the confines of where we stood with each other and ourselves. We carried books as talisman. If you were reading you were safe.

There is one story we did not pull from books that stained our lives as water will linen. It goes like this. One day my mother was in the basement doing laundry. I can see her lifting heavy and stubborn T-shirts and sheets from the tin rinse tub, using an old broomstick to guide the dripping cloth between the rollers of the wringer. I always feared her hand would be caught in the tight gums of that grim mouth, bones flattened along with our jeans. My brother David was home from school that day. All I recall is that David found our mother lying on the cement floor between the whites and colored cottons. This was a fateful fall. She would feel cement against her skull more than once. I did not see my mother again for two weeks; at least this is how it remains in my history book. When my mother returns from what I at the time could only think of as "there," I am told she has epilepsy and I must help more around the house. There would be a more potent invective repeated until it floats to the surface unbidden, "donít upset your mother." Even now, six years after her death, my "telling" calls forth this warning, as if the tides themselves are rising to find me.

It was several days before I understood the plot of the next chapter of my life. It was dusk, the time to roll with the hills to the red horizon; cartwheel upon cartwheel, spinning the earth with my own hands. How I loved the sense of mystery and magic that descended with the sun, the darkness whispering romantic things to a young girl alone at the pasture line, considering the wire boundary between lawn and freedom. I heard my mother sing, "E-LIZ-a-beth," and pulled myself back into skin. I found my mother at the stove, fry pans in place, fixing dinner, again. Even though I had seen my motherís face sour, sour and shape-shift, eyes garaged, neck whipped back, neurons firing in the whimsical way of whatever god plugged and unplugged her circuits until the spine could no longer make sense of the spiraling messages and pitched to the floor, I did not know there was more than the marionette dance and bow. My mother was now making dinner again, staring up at the plain plastic clock there in the hot kitchen, trying to make sense of time, trying to remember her role here, what day it was, what wormhole dropped her at the stove, skillet in hand, at seven p.m. when dinner was always finished and dishes washed by five. And what of the daughter walking through the door taking the pan from the mothers' hand, turning off the burners, making sure fingers and flame remained separate, each stepping into a cold rapid that would carry them far down the river, far into the future, wave upon wave, time and tide.

#4

When I was a girl one of my favorite books was Beautiful Joe, the story of an abused dog taken in by a kind-hearted young woman. Joe endured the whispers and stares of the gentry that came to call at the house of his progressive keepers. Joe knew the difference between pity and true love. Pity lasts as long as butterscotch, love lingers even when there is nothing sweet to suck. I would use this story of rescue and redemption to find a way home on nights when my mother toppled head first into the bathtub, skin scouring porcelain, or when she did a thrust and parry at the grocery store while reaching for a can of cherries. We would deal with each calamity by promptly trying to forget it. Fiction was far more restful than the chaos of everyday life. We tried to soften the plot by saying mother had "spells." It was a prophetic choice of words, for we were all cast dumb, stricken by shame and fear.

I am trying to tell you my mother fell into that book and never came out. That she knew better than anyone how to survive, by continuing to feed the imagination an alternative to what exists; to throw yourself into the larger ocean of life by finding someone or something through story, history, art, poems that carry you into the next minute and possibly an entire day. Something so powerful, so clearly in resonance with your own cells, your own sense of who you really are, the dark side of the moon does not just symbolize the part of your brain that is dead, but the part of life yet to be revealed if you can hang on, hang on to possibility. My mother hung on through many near deaths, riding the tidal wave that rose up within her mind, swamping her, dragging her under, holding her down so she spoke as one whose lungs are filled with water. I know now, Momma. The Phoenicians were more your family than I. They understood, as you did later, when you perhaps remembered or were told how the store clerk handed me his belt to place in your mouth, "lest she swallow her tongue," that when the land is mined out you take to the sea, you make the leap between need and whatís offered by life to stay alive. And so your band fashioned ships that launched an empire, the model from which others drew. When you no longer could find fish close enough to shore, you conjured hook and line, you called forth from nothing a grand something and it fed you, it fed you.

#5

I have never crossed an ocean. I have stood at its hem. I have watched a wave gallop wildly to shore, ending its ferocious ride only inches from my ankle, spitting disdain, but never allowed that steed to spirit me from shore. I have waited for so many things in my life. I have imagined, dreamed, and wondered, but I have not marched forth through the lacy skirt of foam to catch the currents that sweep the seas, until now. As I reel myself back to the present I land a heavy truth. You did not set me down, Mother, in order to pick up a book. You picked up books so you could mine them for courage, the courage to come back on the days you ran away, or later as you clutched my hand, begging me to help you escape the bruised island of your marriage. And in the way a gull takes what today's sky offers, wind or rain, I accept our journey has ended. I know it's time for me to pursue stories long abandoned, to navigate the "nothing-ventured" part of life, knowing my blood runs back in history with yours to the Phoenicians, that I have all I need from you -- courage and imagination. And with this alone I turn and trim the sails toward the sun.

©2004 by Lizzie Hannon