Names, on His Body

by Marnie Webb

We call my tennis partner Princess Pitter Patter.

"It's only because I don't know your real name," I tell her. "Princess Pitter Patter. If I knew your real name."

"L.C.," she says. "What's not real?"

"It's got to stand for something. Lucinda Camille," I say. "Laverne California."

L.C. shakes her head, swings her tennis racquet close to my face. "I'm not telling," she says. "My mother was not nice to me."

She is short, quick feet running down every ball.

From the other side of the court, they call. "Princess Pitter Patter, will you serve now."

"You think you're funny," L.C. tells me. "You aren't. Just so you know that."

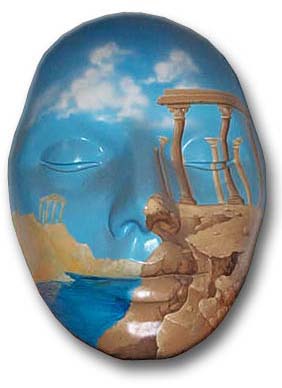

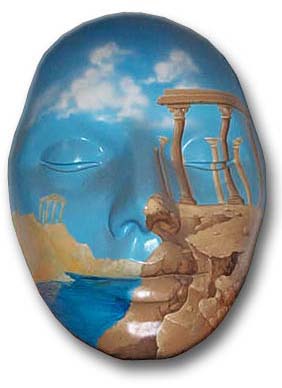

This is part of the Greek chorus of jokes we share. I teach high school English. In my honors class, we just finished reading The Clouds. "This is more real than anything you see in the movies," I tell my students. They do not believe me. They are suckered in by modern production values. "Don't you get the masks," I ask. We spend a lot of time on masks.

I stand in front of the service line replaying my last tennis lesson in my head. I bounce on the balls of my feet, toss my tennis racquet from hand to hand. L.C.'s serve passes my head and is in. I look up. The November light is on the distant ocean and it reflects with an intensity I feel but cannot describe. The return goes past me. I do not even flinch.

After doubles, we go for drinks at a nearby bar. The Point Club is dark and dank and seems transported far from the brilliant light that's capable of stunning me silent and still. The bar is long and the bartender short and the people sitting there are hunched over clear drinks with no ice. Seashells are glued to the walls.

"Four white wines," I tell the bartender. I know what I get will be too fruity. We are slumming. The closed-in must of the room makes me sneeze.

We toast the game. L.C. and I and the Great Avengers. That's what we call Lori and Su but only privately. They win all the games we wish we could. We'd say it to them but we're both afraid they'll take it the wrong way. They claim not to value competition.

They talk about their husbands. I'm single. My bed filled by a succession of women I choose not to name. It is a Saturday afternoon but the Point Club is like Las Vegas. There is no evidence of time.

I decide to talk about my brother. "He's become a Mormon to meet girls," I say. "I think he likes the underwear. I asked him what they believe and he said he didn't know but he was sure they believed in God."

They laugh and we all sip gingerly at the white wine. Lori asks, "Did he give up caffeine?"

"They can drink Pepsi," I say. "The Mormons own Pepsi."

I tell my students that masks are still in use. "Look at makeup in movies. Body doubles. The physical work those actors do to become someone else. They're just trying to trick you out of believing it." My students believe the actors and not me. I'm going to test them on masks. I'm going to ask them if makeup and hair color and weight training is a modern equivalent to Greek masks. It'll be a true or false question.

The woman I am currently sleeping with is a computer programmer. She kisses my belly and then rests her cheek on me and sometimes falls asleep there. I touch her hair and move the covers to look down the naked curve of her back, the rise of her hips. It is like the fall of light on the tennis courts.

Driving home after the Point Club, I say, "Lindsay Carousel."

"Did your brother really become a Mormon," L.C. asks me.

I nod. The sun has started to fall and the glare is fractured and magnified by the smear of dirt on my windshield. I squint against it and try to see the road. "If someone crosses in front of me they're dead. They have no hope."

We turn into the curve of canyon that leads to L.C.'s house. She has invited me to dinner again. She worries about me, thinks there is no one to take care of me.

"But not for the underwear, right?" She means my brother. "That part is a joke."

I shrug. "To meet girls is true. Do you think I would kid about God? I hate this time of day. I can never see anything this time of day."

One side of the road is hill and the other is a sloping drop into Santigo Canyon. I look down dizzied by the distance, the dirt trails that criss-cross the sides. My car moves into the on-coming lane. The hillside houses are built on stilts. They have no chance of surviving disaster. Their views must be worth everything. I pull back to my side of the road.

I know my computer programmer is waiting for me. I want her to be naked and in my bed. "I don't want to have to talk," I said to her on the phone. "I just want to come in and find you there."

"Are you sure no dinner," L.C. says as I pull into her drive. She thinks I go back to my home, empty and alone, and am sorry I don't have the family and lives of the women I play tennis with. I do not correct her.

"Lucita Carol," I say. "Get out of my car."

The Mormon desire is true but that is not the real thing about my brother.

My brother has the names of seven girls carved into the inside of his left forearm. The names of nine carved into his right. They are angry scars on tender, hairless flesh. The veins at his wrists pushing up into the "d" of "Amanda". He uses a buck knife given him by our grandfather. He wears short-sleeved shirts. I can barely look at him.

In bed, later I am running my fingertips up and down her spine. "Baby," I say. "Oh baby."

"Say my name," she tells me.

Instead, I try to explain the light. "Maybe," I say. "That's why movies started here. Is the light like this everywhere? It's just that there are some days. Some days."

She leaves and my house feels as empty as L.C. imagines it. I wonder around flashes of my brother. I have begun to fear the ringing phone. I try to think of my brother as a literary problem. That's something I am good at. I try to think of the author's intent. I do not know the author.

My brother answers the phone on the first ring and I am quiet. I consider hanging up. He says, "Who the fuck is this?"

"Don't you have any patience," I ask him. "What if it was mom?"

"Why should I care?"

"What are you doing? Do you want to do something with me?"

"What?"

I close my eyes against the image of his arms. When I think of those scars, I see him sitting there. Hunched and alone. Is he in the bathroom? I put him in the bathroom. Nothing to stop the slip of blood from his body. The floor spotted at his feet. His legs freckled in red drops. Blood caught on the curling hair of his shins.

"The movies." I do not know what he likes to do. I cannot imagine the boy I knew: names cut into his body. We make plans. A date for the next day. After my Sunday morning tennis.

When I hang up, I call my computer programmer. I want her to come back.

When she gets there, smiling and surprised, I try and tell her again. "It's like for one instant," I say. "I do not even know who I am." I do not tell her about looking down the covers at her. About touching her sleeping head.

I say, "I'm going to make them read Faulkner. They think they didn't like the Greeks. Wait until they read him. Not just "The Bear." I'm going to make them read a novel. The Sound and the Fury.

She moves against me, skin on my skin. We have not made love. My bed has begun to smell like her breath. I put the covers over both our heads.

"When you turn computers on," she says. "There is an instant when they do not know what they are. They run a check. For memory and resident programs, keyboard and printer. They reach out and rebuild themselves every time they are switched on. Maybe that is what the light does for you. Maybe that's what you are talking about."

I pull back from her. The covers tent above us, my head the central pole. "How did you do that? I can't believe you just did that."

"What?"

"What you said. I can't believe that. That's amazing."

"You think books are the only way to understand the world? Faulkner and masks."

"Yes," I say. Back down next to her the sheet and blankets settling into folds, pockets of humid air around us. "In fact, I do."

"You're wrong," she says, her mouth so close to me the words bounce off my skin. The distinct edges of sound blurred by our nearness.

"Self-checks and correction," she says. "Nothing knows itself. Even computers. Everything is constantly surprised by itself at the moment of reawareness."

"Are you a Buddhist," I ask.

"Presbyterian," she says. And we fall asleep together, sweaty and wrapped in covers.

In the morning, L.C. and I tell the Great Avengers we have set up a match for them. "Against those two," we point across the club courts. Two women in matching tennis skirts are warming up the right way. Standing inside the service line and hitting gentle balls, moving further and further back. We lost to them in a round robin two weeks ago.

"They high-fived afterward," L.C. told me. "I hate that."

"The Great Avengers," I said.

"The Great Avengers," she said.

L.C. and I play singles and sneak glances at the game. We hide our interest. We do not serve when we play each other. We see how long we can rally.

"Louellen Carsonita," I say.

"That's not even a name," she calls back to me. "Carsonita. And Louellen."

"I'm thinking horrible. It's got to be horrible."

We have been doing this particular joke for three years. I'm sure I have repeated myself.

"Linda," I say. My eyes are closed. I'm looking for the "C" on my brother's arm. I do not know. I run out. There is no light on these courts, reflected ocean. We are dropped in a tiny valley; the hillsides cup around us. PCH, a constant whoosh through air, behind me. I do not rebuild myself. I stay stuck in this moment. "Glitch," I say thinking of my computer programmer.

"Doesn't start with a ‘c'." She is not with me. "You're not even close."

I let the back and forth of the ball lull me into something like comfort.

Afterward, L.C. and the Great Avengers head to the Point Club. I say I will not join them.

"Why," they all ask. "Just for a few moments."

It is not possible, in the stream of our patter, for me to tell them the truth. "Family," as close as I can get. The word rings out in the distance between us.

I walk L.C. to her car. "Do you ever wonder," I ask. "That we don't really know each other. We just go over the same material."

"Are you talking about my name? I'll tell you my name if it really bugs you."

I shake my head. "I've got to guess. Lucille Carmilla."

"You were right once." She snickers at me. She is in my shadow. "You didn't even know. I didn't give it away."

There are lines here that I know I am supposed to say. "Really," is all the energy I can muster.

My brother is waiting for me. Short-sleeved shirt and anger.

"What movie," I ask.

"Why," he says. "What are trying to talk me into?"

"Are you seeing someone," I look for something new.

"You don't do this," he says.

I move close to him. The sweat sharp smell of his body. Blonde hair hacked hard and it occurs to me, for the first time, that he chops the hanks of his hair with the same knife he uses on his skin.

With one finger I touch him, poking into his shoulder, the bounce of an irritating child. There is nothing for me to say. I fall back upon childhood embarrassment. "My ears still stink," I say. "Like always. The wax builds up and my ears stink. I swear to God I'm standing in front of a class teaching and I smell the stink of my ears. Do yours?"

He looks at me in surprise. I cannot tell what it was he expected. "I don't know," he said. He touches his lobes.

"Here." I thrust my head at him. Ear near his nose. "I stink."

He sniffs. "Oh Christ," he says. "You're right. Oh God." He touches his own ear again and smells the tips of his fingers. "I can't tell."

I turn to the side of his head. The tip of my nose against him. My lips brushing his jaw line. I close my eyes. I don't know how many more chances I'll have. Blind, I touch the inside of his arm. No longer words, now the geography of his torment breaks my heart. I breath in.

"You smell," I tell him. "It's disgusting. Has anyone ever told you?"

"Has anyone ever told you?"

We are standing near a window. The fall-angled sun leaking around the curtains. There is no hope, I think, of rebuilding myself here. Of reaching out in a way that identifies him as still a part of me.

"Why do you do this?" My hand on the ruptures of flesh.

My computer programmer is right. I have no hope even of knowing myself. Building and rebuilding with each awakening. There is no way I can know him. Names and scars. Imagined blood and desire. I cannot even come close to stripping away the masks we devise to both identify and deceive. My brother is not a literary problem.

We stand together awash in a diffuse and perplexing light.

©2002 by Marnie Webb