Maniac Island

by Mark Kline

Wilfred is explaining star structure while munching on Italian almond

cookies. His teeth are continually exposed. Immaculate teeth. I am

watching his mouth, which I feel entitled to do, as often as he eats

here. He talks while chewing, and vice versa. Either he frowns like he

just bit into a tarantula, or he stretches his lips into what I have

acknowledged to Gina must be a smile.

He could be mistaken for an Italian. He combs his wavy black hair

forward from a volcanic whorl on the back of his skull. But he is from

Germany. Or as he once explained, "Actually, Schleswig, or actually the

Wadden Sea, on an island full of birds flying over all the time,

migrating, always migrating! A maniac island! And you can wade through

the sea over to it!" An Italian would have illustrated this with his

hands, but it was Wilfred's head that tilted to watch the flight of the

birds, his chin that pointed the way to the island.

For supper Gina fixed smoked ham with rice flour dumplings, his

favorite

childhood dish. Her goal was to put him in a positive frame of mind.

"We need another outlook on this situation," she explained to me yesterday,

"and you know how intelligent Wilfred is. And he's not afraid to say

exactly what he thinks."

"Yeah," I said, "neither was Hitler."

So here we sit after supper, around our kitchen table. This is where

Wilfred keeps us up-to-date on reality. Coffee, cookies and cold stars.

I can just see Wilfred on Letterman's show. "All right, everyone in the

audience who believes the universe was once the size of a beach ball,

raise your hands!" Gina can't stand Letterman. He reminds her of half of

the boys in the fifth-grade class she teaches. Not the better half.

She says she is concerned about my condition, very concerned, and she

should be. I'm hauling in most of the bacon around here. But I know

she'

s hoping for more than advice. She wants an Explanation. She wants

Insight. Enlightenment. And Wilfred the physics teacher has Theories

that cover it all.

To tell the truth I want to hear Wilfred's spiel too -- what's he going

to

say about a man who for three days now has been hearing the same

country

song two-step through his brain, day and night, not one single pause in

the action, not one variation in a solo, not one warble left unwarbled?

Maybe he'll lick his teeth and tell us that one of those microscopic

black holes floating around the galaxy has entered my brain and the

song

keeps skipping off its horizon like a stuck record. That it's sucking

my

brain up, too, and will continue to do so until the end of time,

provided

the universe stops expanding, but it doesn't appear to be, please pass

the cookies.

I used to listen to country music before we were married. Gina is

against it in principle -- "It's for birdbrains, minus the brains," she

says. After hearing a man wail about a waitress with a ribbon in her

hair a couple hundred times a day, I see her point. This song contains

two chords. The electric bass plays a total of three distinguishable

tones. By contrast the melody is a fountain of variety, a real gusher.

The whole thing smells, no kidding. I passed through the kitchen while

Gina was working on the ham and took a big whiff during the second line

of the first verse. Now every time that line comes around I sense a

tinge of the ham's grittiness, like salty regret, deep in my nasal

passages.

And then there's the ping-pong effect. I was in the bank yesterday to

finalize a loan with old man Steerman, the bank vice-president. The

butterflies in my stomach went stir-crazy during the last chorus, while

I pretended to understand the fine print. Then when Steerman leaned

over

from his side of the desk to make damn sure I signed my life away on

the

right line, his Old Spice hit me like a trade wind. Now the end of the

song sets the butterflies to flying in my gut again; then the aroma of

this morning's toilet bowl cleaner fills the short pause before the

intro kicks off again, which brings on the Old Spice. The long and

short

of it is, now I'm skittish about walking into the bathroom. Steerman

may

not be in there, but try telling that to my stomach.

And this morning. When I shut the mower down I drew in a long breath of

cut grass. Best smell in the world. I felt great each time the end of

the first verse came around. Now that's already been obliterated by

Gina's vinegar cure for mildewed shower curtains, which drives me out of

the

house. Out of my mind. I wish I could drive out of my mind. There's a

principle at work here that I'm sure Wilfred would enjoy explaining -- why

everything in the universe tends to go to hell. I could stick a

clothespin on my nose.

Gina sets her coffee cup down. "There's something Paul and I would like

your opinion on, Wilfred. It's a...." She smiles at me,

optimistically. "Well, a unique situation, really. Tell him, Paul."

I twine my fingers together and lean forward on the table. "Wilfred,

it's like this. I keep hearing this song in my head, non-stop, twenty-four

hours a day."

We sit for a moment. Wilfred looks at Gina and starts to laugh. Nothing

he does is ever half-ass, I'll give him that. He's the only man I know

who cackles. Gina strings him along with a smile. "Come on, Paul,

really! Explain it to him!"

"All right then, let me put it this way. Wilfred, I keep hearing this

song in my head, twenty-four hours a day, non-stop."

He lifts his eyebrows and begins to scrape the skin just below his lip

with his upper teeth. He has a heavy beard. It must sound like a

distant

fire to him, the kind that makes you sniff the air to detect what's

burning and from which direction. It could be a garage, an old house on

an empty lot. The second verse ends. Next time around I bet I'll smell

smoke, a sour, smoldering rotten wood fire. My eyes will water. The

song

zeroes in on disaster, imagined or otherwise. Fires spread so easily

anyway.

"A song," he says. "What exactly."

He pauses, frowning. Then he turns to Gina. "A song?"

Gina takes over. "It's a country song. It keeps repeating itself over

and over in his head and we can't do anything to stop it." She bites

her

lower lip, trying to think of what to say next. "I tried the hiccup

cure. You know, coming up behind him and screaming. He jumped a mile."

Wilfred cackles. "OK, this is a joke!"

"Wilfred, you know I don't play jokes like this!" This is vintage

Gina-flying-off-the-handle-in-a-civilized-manner. "I am so...angry,

that something like this could happen! We don't even know what it is,

for God's sake!" Gina never curses. "Is Paul sick? Is someone

responsible? Who's going to help?"

The following silence pulses between the lines of the last verse. The

front beat turns backbeatish. It's as if I were watching a film and

suddenly it began showing as a negative print.

Finally Wilfred hmmm's a few times. "What song is it?"

Gina sighs. "He's not sure. He thinks he's heard it somewhere, but I

haven't heard of it before."

"You mean, you've, what -- haven't heard it?"

"Of course I haven't heard it! He told me the title, I've certainly

never heard it, but we don't listen to country music, you know that.

When I say I haven't heard of it," she adds, in her clarifying,

Wilfred-isn't-American voice. "I mean I've never heard it on radio or

anywhere; I didn't know it existed. I haven't heard it or heard of

it."

"OK, then how do you know, you know, that it really is a country song?"

"You know what country songs are like, Wilfred! All those idiotic hats!

Tearjerkers, fiddles -- there is a fiddle in it, isn't there, Paul?"

"Look," I say, "why don't you go get the headphones and plug them in my

ear, we'll all listen together." Gina glares at me.

"How long is it you're hearing this song in your head?"

"I woke up with it three days ago."

"OK. Maybe something really strange happened to you before, or

something

in your sleep you're not knowing about."

"Yeah, maybe I got beamed up by a UFO, maybe they redid my brain, left

a

wrench in or something." Which is not so far from the truth, only the

UFO -- a parasite -- came down to me. Somehow it organically recorded the

song and wormed its way into my mind. It's a space parasite, obviously.

Earth parasites are millennia away from this type of capability.

Gina speaks in low, crisp syllables. "I wish you wouldn't act so

childish and sarcastic, when we are concerned. When someone is willing

to listen and possibly even help, and you think you're being witty."

"You're the one who believes in UFO's."

"Paul." The middle of the guitar solo slides by, knife-sharp. The

sustain on the guitar clears the air between us. Her eyes play every

note.

"What I'm getting at is, is where there's smoke you get fire," Wilfred

says. "Songs aren't just creating themselves, you know."

"Why not, the universe did," I say.

"You have heard it somewhere, maybe!" He's rocking in his chair. "Maybe

you're creating it out of your mind, in your unconscious. Maybe there

are problems you're not knowing about, who knows, you don't even know!

Why don't you visit a psychiatrist?"

Gina holds still, staring at a point beyond Wilfred. It's a dead

giveaway. Either she's been thinking the same thing all along -- I had the

feeling this morning when she slid out of bed, the way she turned away

from me, that she might be thinking "shrink." Or -- the thought comes to me

now -- maybe she has already let Wilfred in on all this, and their

strategy was that he would play dumb for a while, then toss the

suggestion out.

"Really, that might not be such a bad idea, Paul. It's possible a

psychiatrist will have heard of something similar to this."

"Or tinnitus!" he points out. "You don't have to be nuts to have

tinnitus!"

Gina jumps in. "Nobody's talking about nuts, Paul!"

Just as I thought. I'm at the last line of the last verse, and that

eerie negative-printish feeling comes over me again, everything gets

turned inside out. Everybody's talking about nuts, Paul. This

parasite

has a wonderful sense of timing, I'll give it that.

"Who knows!" Wilfred grins. "There may be several cases of people with

some guy singing, you know, in their head. This doesn't have to be so

weirdo."

"I never said it was 'some guy,'" I say.

"Gina said you didn't know who was the singer."

"I don't know who was...or is, I mean. I just never -- I never said...I mean I just said that I never said..." I stop. I could laugh

right here, and if I did then Wilfred would laugh, then Gina would have

to laugh, too. We could all be laughing right now. We could turn this

into a real swinging party. But now the intro is over, and I'm

distracted by the brackish odor of bird balls from outside our window.

The smell of the future.

Gina sighs and rubs her temple. "We discussed seeing Dr. Simpkins, our

GP, but we're not convinced he's the type of physician who would keep

an

open mind on something like this."

"Definitely. Definitely keep an open mind, and I know Simpkins, one of

these guys on the Medical Arts bridge team, they go with the book, you

know, never take a chance, forget him! Break your arm, great. Go to

him.

Tell him all day you're hearing a song in your head, you know, he can't

help you. OK, maybe he'll say go to a psychiatrist but you already know

that."

"We considered the possibility this is some sort of sicko joke, that

someone stuck one of those tiny receivers behind Paul's ear last

weekend. He filled in at Boy Scout camp. Really, some of those boys

need

a much more structured and caring environment at home. I've had several

of them in class, I should know."

It had been her idea. A crazy one, I told her, but she insisted on

searching my head. It reminded me of Mom checking for ticks, Gina's

fingers gently pushing, parting tufts of hair and pausing, then moving

on. It had felt soothing at first. But her fingers began rustling

around

impatiently, spider-like, as if I were hiding something from her. She

began kneading my scalp with the flats of her thumbs, first around one

ear then the other, then carelessly slapping my hair down with her

fingers. Finally her hands broke contact with me altogether, and I half

expected to feel a whack on the side of my head; this happened at the

end of the second block of solos. Now, at that point in the song, a

bronze-like film of fear cases the back of my throat and runs up into

my

temples. It makes me shiver.

Gina sighs and scoots her chair back, she pivots and walks back to the

kitchen cupboards. Her skirt swishes, like slow ribbons. The last line

of the song passes. "Slow ribbons, the way I fall for you." Slow

Ribbons. That's the title of the song, I'm sure of it. I can picture

them now, the ribbons, I'm holding them, light in my palms, they tickle

when I pour them from one hand to the other. They're faintly scented

with perfume. Lilac, I think. Yes. I have to concentrate to hear them

rustle against each other, a tiny sizzle. I tilt my hands and watch

them

trickle down. They fall in formations, slithering in crimson curlicues,

covering the song.

Gina holds three cognac glasses in her hands. She butts the cupboard

door shut with her head. She sets the glasses down in the middle of our

beautiful round wide-grained oak table. She opens the liquor cabinet

and

grabs the neck of the cognac bottle and plucks it out of the array of

liquor and whiskey without a single clink. I'm in awe of her, it's an

amazing feat. But there's also something melancholy about it; it's like

a giant thumb and finger pinching a beech sapling and pulling it

straight up through a tiny gap in the forest's canopy. A silent,

deserted forest. That tree's gone forever, and no one will ever know

it.

She sets the bottle down, label towards Wilfred. Napoleon. She slumps

in

her chair. Gina never slumps. She looks like a worn-out mother. Wilfred

is deep in thought, an incredibly contorted frown squares up his face,

his upper lip presses down on his lower teeth. They look like the

parents of a perpetually naughty child, they're wracking their brains

to

come up with some solution so they can get their lives back on track,

so

they don't have to think about the little jerk anymore.

We stare at the glasses. Their concave bases distort the wood grain,

making it rise and stand out like a smattering of wild rice on the

table, wild rice native to marshes and northern lakes that famished

birds glide down to. The rice has a pecan-like odor while cooking, the

steam licks my nose.

"I forgot," I say. "I've got to get the water started on the tomatoes."

I rise and walk straight out the back door. No one says a word. No one

has to.

Halfway to the garden the realization hits me like a solar wind, silent

and invisible, leaving me electric. I know the singer! It's Fred

Seagull, the Biggest Country Star in the World. 360 pounds. Immediately

the song stops! I'm stunned -- another rush, my nerve endings whoosh from

my gut to the top of my head. Then I feel the quiet. It's creepy, like

suddenly I'm somewhere else but it's not somewhere else, I'm right

here,

the silhouettes of the trees and the clothesline posts haven't budged

an

inch, but right here where I'm at feels like somewhere else.

Behind me in the house one of them says something -- I can't tell who from

here, Wilfred is a tenor -- when the music starts again. Ribbons of steel

guitar swell then narrow, they rotate and swoop down. Strangely enough,

I don't catch that it's a different song until a woman begins to sing;

or a girl, rather, a teenage girl. I know this song, it's on the tip of

my tongue. A man comes in on the chorus, now it's a duet, and the title

of the song is a dead giveaway. It's a slow, countrified cover of

"Islands in the Stream." I get it. The parasite is playing "Name That

Country Tune and Singer" with me. It has a great sense of humor, I'll

give it that much. I wonder how many songs it's stored up in its

organic

digital memory? When the other parasites touch down -- there must be millions, billions of

them -- what will the one that sets up shop in Wilfred's head play? Name

That Polka and Tuba Player?

I shove the hose under the mulch of wheat straw, then I turn the water

on at our garden well. I crane my neck to the circles of stars and

listen. I close my eyes. I feel long, strong chains of birds migrating

above me, straining soundlessly. People wade across a suncovered sea

towards me, singing a song. It's low tide off Maniac Island.

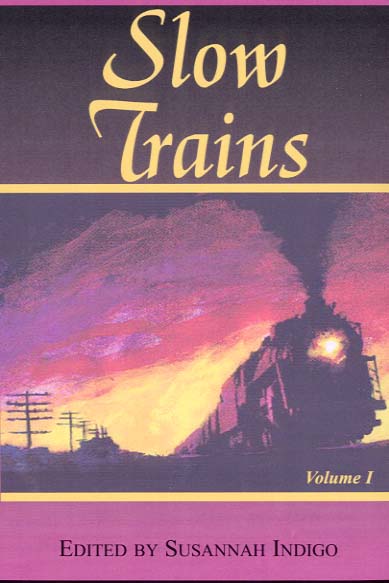

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print