Margaret Coulson

Nowhere Train

The instructions in the email had seemed at once straightforward and exotic. Arrive at Pudong. Catch a taxi to Hongqiao Station. Buy a ticket on the G train to Haining West. Pudong. Hongqiao. Haining. Unfamiliar places that evoked a pleasurable sense of adventure. She had not yet thought about it enough to be nervous or fearful.

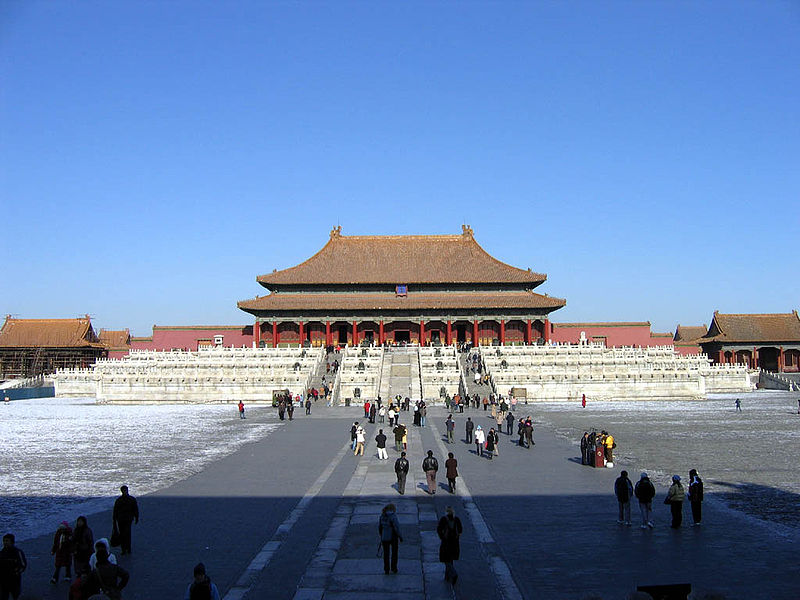

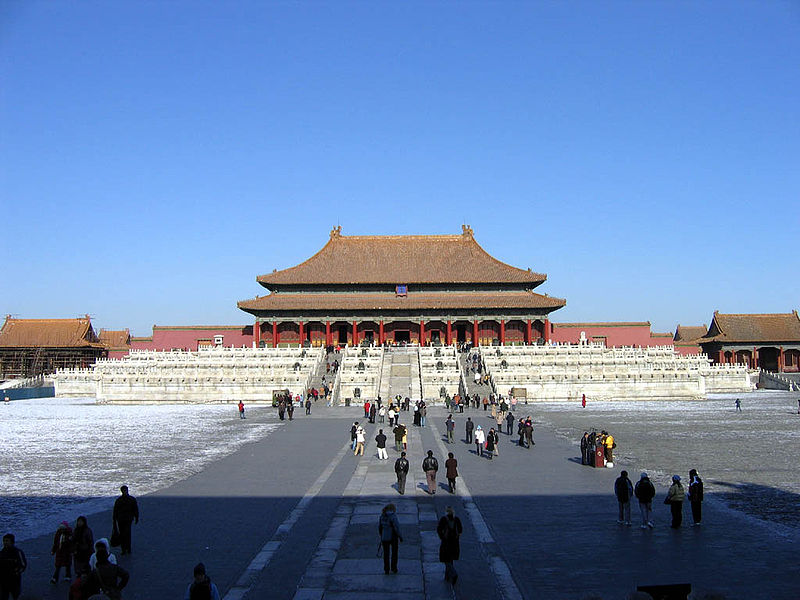

Mindy’s friends had all been delightfully shocked when she announced her decision to go teach in China. They were even more flabbergasted when she told them where. Haining. Not Shanghai. Not Beijing. Not a place that appeared on the weather maps after the evening news. Not a place that could conjure images of Mao suits or great walls or parades or pandas or jazz clubs or gangsters or impossibly tall buildings. A non-place.

Mindy was searching for a non-place. A place to leave her former self. The hospice nurse. Mother of two. Dutiful wife. Quiet friend except on hens’ nights. Fifty-year-old with a spreading bottom and cankles. Early morning beach walker collecting unusual shells. Homemaker with French Renaissance prints and Turkish rugs scattered throughout the house. Regular visitor to the National Gallery in Canberra. Fan of Nick Cave and Tom Waits. That self. That former self. That self that had been merely an illusion of her place in the world, a shifting speck of sand that thought it knew where it belonged on a sunny beach until one day a windstorm twirled it into a place it did not recognize.

“Is that even on Google Earth?” asked her best friend and neighbour Vanessa in bewilderment. Vanessa with her long red nails and lime green maxidress and successful catering business scrolled her Macbook looking for a geographical foothold on her friend’s madness. Vanessa whose husband still came home every night. Vanessa whose children still came for barbecues every Sunday.

“It has the Qiantang River wave, the world’s biggest tidal bore,” Mindy told people knowledgeably. In fact, this was the only information about Haining she had been able to glean from Google. She liked the idea. From the waves of Bribie Island to the world’s longest wave. It had a certain synergy.

He left. There was nothing more to be said. A simple two word summary. Ten days after her fiftieth birthday party where they had invited everyone they knew and ate copious amounts of prawns and danced beside the pool to a jazz quartet and drunk too much Shiraz, he left. There was only emptiness and a house to pack up and sell. In fact, she packed little. Just her clothes and a few mementos.

Ben and Louisa came and selected everything they wanted or needed. She gave most of her jewelry and ornaments to Louisa who took one of the best display cabinets to her latest boyfriend’s house and put everything there for safekeeping. Ben had taken some pieces of furniture and crockery to round out his bachelor pad. Neither of them wanted the childhood toys or books she had so carefully treasured. Vanessa’s eagle eye spotted an unused wedding gift from thirty years earlier in the wreckage. A crystal cake server. Quite exquisite and perfect. Too perfect with two children and their play dates running through the house. Later, it had been superfluous with shift rosters, sports carnivals, teenagers splashing in the pool, a husband who got regular emergency call-outs for his job at airport security, taking care of her ageing parents till they died, stolen drinks with friends in between. There had never been space in her life for a crystal cake server.

After she had packed the basics and given things away, Mindy kept nothing. For a month, she diligently sold items on eBay, held a garage sale, advertised in the weekend shopper. She gave all her linen to the hospice. Everything else went to the Salvation Army. They came with a big red truck to collect it, loading the sum parts of her life into the back with the discarded remnants from an old lady who had died last week, according to the driver.

On the afternoon that the house was auctioned, Mindy had walked barefoot in the sea, icy water forming rivulets around her ankles, winter sun strong enough to force her to squint, an occasional splash from a lone boogie boarder paddling nearby, eager pelicans flapping near the boat ramp in hope of an easy feed, the Glasshouse Mountains rising timelessly in the background. She had expected to be here forever, unchanging, like those solid, salient pieces of rock. Tourists always think they are so-named because the bare stone jutting into the sunlight reflects like glass. Any Queensland schoolchild worth their salt knows that they are so-named because Captain Cook thought they looked like the glass-making furnaces from home. In fact, apart from the fact that they were both conical in shape, Mindy had never been able to see much likeness. She pondered that even a man as steadfast and strong as Captain Cook had been prone to homesickness. She wondered if anything in Haining would remind her of home.

They had been deliriously happy the day they bought the house. A weatherboard beach house, bought before the island became trendy, tenderly restored and extended and renovated over the years as the children grew and tastes changed. Five star resorts, coffee shops, shopping centres, retirement villages, new-agers and real estate speculators moved in. Their beachfront home remained a steady haven through the years. That night, they had sat on the beach, stared at the lights on the bridge, drunk cheap cider, made slow, quiet, agreeable love on a mattress on the floor.

Vanessa drummed her nails on the steering wheel as she drove to the airport. “We can turn back,” she said.

“No way, go for it Mum shouted Ben from the back, fisting the air like it was a rugby match.

“It’s great Mum,” yawned Louisa who clearly wasn’t dealing well with the early morning activity.

“Your roots need doing,” grumbled Vanessa. “Do they even have hair dye over there?”

A final glance of concern from Vanessa, perfunctory hugs from her beautiful, gregarious, clever, independent offspring and Mindy was swallowed into the Departure Lounge. She checked her documents. Dozens of times. The furthest she had ever flown was Alice Springs. She tried not to think about the changeover in Hong Kong. Around her there were indifferent businessmen gulping coffee, children like her own with backpacks and tablets, women with headscarves, entire families crowded around little circles of luggage, prim airline staff waiting for clearance, people laughing and discussing and arguing in languages she did not understand. None of them were checking their visas, passports, boarding passes.

Mindy slept soundly on the plane as the precious bag carrying her documents fell to the floor. She had awoken in panic when the airline steward put it carefully back on her lap. He had looked at her with a warm mixture of pity and paternal concern. “We’ll put it up here,” he’d said firmly, opening up the overhead locker. She had felt chastened, small, comforted.

Mindy had successfully negotiated the changeover in Hong Kong with a resolute determination. She tried to look like a woman who did this all the time, walking briskly towards the shuttle signs, not fumbling or checking anything. She found her gate, had time for a coffee, felt almost worldly as she waited for the boarding call.

She was seated next to Rick from Canada on her Dragonair flight to Shanghai. He was about the same age as Ben with the same wooden plug earring in his stretched earlobe and tatty jeans. Like a travellers’ uniform for twenty-something males the world over, she mused.

“Welcome to the club,” he’d said with genuine enthusiasm when she told him she had a job teaching English.

“Ah, the Qiantang wave. It’s sick,” he’d said when she told him where she was going. Rick from Canada had heard of Haining she noted with pleasure. He had stories about girls, bars, crazy students, corrupt employers, strange food, wild taxi drivers, house explosions in the night and visa runs. He seemed to be an endless fount of knowledge. She wanted to ask him about hair dye and how a hospice nurse might go about teaching kindergarten children in a place no one knew. But, she felt this did not fit with her new worldly persona and swept her queries away.

Mindy filled out her arrival card cautiously. She meticulously wrote the address given to her and ticked “visitor”. She practised the story in her head. She was visiting an old family friend in Haining. Mr Xu, her employer, would get a work visa later. It had seemed so reasonable when he explained it on Skype.

“Oh yea,” Rick reassured her. Quite normal. I’ve just been to Hong Kong for a visa run myself.”

Mindy felt faintly excited. She had become a worldly woman who did visa runs. Vanessa would be mortified.

Her luggage felt heavier than she remembered when she pushed past the crying children, men with overloaded trolleys, women shouting into mobile phones, and heaved it from the conveyor belt. She sweated with nerves and a little weariness as she reached the immigration desk. She stumbled, dropped her passport, retrieved it, mumbled her story without being asked, fumbled for her entry card, knocked over her suitcase almost hitting the grandmother and toddler behind her. The officer barely glanced at her or her passport before taking a photo and waving her away. A faceless, middle-aged, invisible nonperson. In Australia. In China.

Back in Australia, Mindy had cultivated a spirit of glamorous notoriety amongst her friends and colleagues. They were partly aghast but mostly in awe of her decision. She had felt buoyed by the whiff of rebellion her action implied. Now, she didn’t feel glamorous or rebellious. She just felt lost, weary, sticky, wrinkled, graying, foolish, ready to collapse.

“You don’t have to do this to spite me,” was one of the few things her husband had said.

She had tossed her head and exclaimed in her best Gloria Steinem protest voice, “I’m doing it for me.”

“Taxi? You want taxi?”

She swatted the pestering groups of men with yellowing and missing teeth aside. She forgot about her worldly persona and hunched raggedly as she dragged her baggage through the arrivals hall, then out the door to the taxi rank. The bolts of heat hit her. Not the blue-sky, Queensland heat that she had tanned under all her life. A nasty, gritty, grimy, pore-clogging, stench-inducing heat that burned through her T-shirt and jeans like a rusted branding iron.

Mindy winced and cringed and inched her way along the line until at last it was her turn to be gestured towards the ageing blue Santana with a driver who nodded, grunted, burped and sped off after she gave him the printed address for Hongqiao Airport and showed him the location on the GPS app Ben had helped her download onto her i-phone. She peered into the front seat to see if he showed any signs of uncertainty, but he was busy shouting into his mobile as he swerved and honked and overtook concrete trucks and ran red lights and ignored pedestrian crossings in a manner that definitely suggested he knew where he was going.

Mindy suspected it wasn’t the shortest route, but she didn’t mind. They passed gleaming silver, stark black, gold speckled, harsh grey, pink metallic striped, fantastically shaped skyscrapers that threatened and inspired worship whilst permanently floating in a low-level mist of semi-opaque, indiscriminate colour. They passed picture-book tiny cement farmhouses with little vegetable gardens and large piles of rubbish. There were impossibly high extension bridges that rose above invisible waters below and narrow bridges that allowed a birds-eye view of tea-hued canals and overloaded, rusty barges. They sped past shopping malls with Swarovski Crystal, Ermenegildo Zegna, Versace, Zara, Burberry and Dior. There were restaurants the size of hotels and food stalls the size of a desk. They fled through the inner city and suburbs alongside Mercedes, BMWs, shiny vans, ancient trucks, bicycles, scooters, buses and pedestrians who waded nonchalantly through it all. It made Brisbane look like a mere plaster-cast model in an architect’s display case. Bribie Island would simply be a pinhead dot on the model.

At last, they exited a ramp off an expressway and Mindy saw another square monolith, not unlike Pudong Airport.

“Now stop,” said the driver.

Mindy gave him three shiny red notes from the pile of money she had exchanged at her local bank before she left. She had been thrilled by the newness of the notes with their Mao Zedong icon and even more impressed by the huge pile. The young bank teller with too much eye liner had looked efficiently bored.

Once again, Mindy hunched as she ploughed into the station. Her luggage went through a scanner and then she was faced with a cavernous hole of a space. There were signs pointing both East and West that said “Ticket Booth”. She dragged herself to the East. There were only ticket machines that she could not possibly master. “That way,” pointed a young, studious-looking man as he saw her shoulders droop. Mindy pulled herself, her luggage and her flailing spirits towards the West. More lines. More waiting. At the window, she handed over the address for Haining West and showed it on her i-phone app.

“Huzhao ,” said the girl with the same efficient boredom as the bank teller on Bribie Island.

Mindy looked blankly.

“Huzhao, huzhao,” the ticket girl’s voice became louder.

“Passport,” screeched one of the other ticket sellers.

More fumbling, more red notes and at last a small rectangular blue ticket to somewhere.

Mindy started showing her ticket to random people and going in the direction they pointed. A security guard. A woman with a baby swaddled on her back. A group of students in uniform. Finally, when Mindy felt she could walk no further, a tottering teenager in short, tight skirt and ultra-high heels pointed at a number on her ticket and the number on the gate in front of her. She pushed through the turnstile. Almost there.

The train was more comfortable than the airplane. Mindy leaned back and checked her phone for the first time since she left Brisbane. Her children had researched and argued and researched some more until they finally decided on an international phone package for her. She was grateful, but she hadn’t really cared.

183km/hr

Ben: U alive?

210km/hr

Louisa: U must be well and truly into yr new adventure. Hope heat not killing u. Let me know when arrive. Work sux as usual. xx

250km/hour

Vanessa: How are you doing you poor darling? Are you all right? Let me know if there are ANY problems. I am here for you day or night.

Mindy leaned back in her seat and faintly acknowledged the passing countryside through the stark afternoon glare. More tall buildings, smaller buildings, ramshackle buildings, pagodas, temples, piles of nothing, expressways, dirt tracks, smokestacks. Muted, dusty, dirty colours with the occasional startling slash of neon pink or lipstick red or emerald green.

It was late afternoon when she was deposited at Haining West station with a handful of others. The station was a miniature version of the one at Hongqiao, all concrete and gleaming tiles and massive glass windows and vast unused spaces. Hongqiao however, had been crowded and bustling; this station was quiet and almost empty. Down an escalator, through a tunnel, up some stairs.

Beyond the station windows, there was a massive car park. A lone blue bus sat at the bus stop. Further past the car park, there were farm fields and a few shabby houses that might have been a village. A long, straight road stretched towards the horizon.

The arrivals and departure lounge only had a few staff in crinkled uniforms who now eyed her curiously. Hot tears welled behind her eyes.

“Ni qu nar?” One of the uniformed girls stood before her.

“Does anyone speak English,” rasped Mindy.

She had Mr. Xu’s email address. She had Mr. Xu’s Skype address. She had no phone number, Mindy realised with rising panic. Other staff members came forward.

“Ting bu dong.”

“Keyi shuo zhongwen ma?”

“Ni deng shei?”

Mindy found herself in the centre of a growing circle, despite the fact that the station had initially seemed so devoid of life. Frantically, she produced the email address. Much shouting and calling and gesticulating, then someone disappeared with the piece of paper.

Mindy fought to drown out the scene around her. She thought about a time long ago when she had travelled by slow train from Brisbane to Bundaberg. Bedraggled and heartbroken, she had arrived at two in the morning, telephoning her father from a public phone box. Within minutes he had arrived, all smiles and quiet business as though it were perfectly normal for his nineteen year old daughter to show up unannounced at an ungodly hour.

She looked past the crowd and out the window again. The road ahead remained stubbornly empty.

©2014 by Margaret Coulson