| Fiction | Essays | Poetry | The Ten | On Baseball | Chapbooks | In Memory |

|

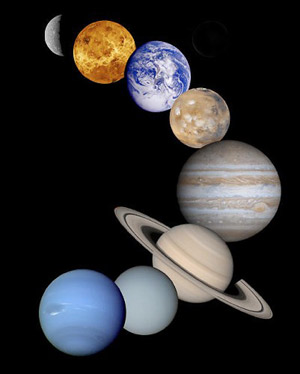

“Can I look in your microscope?” the boy asks. He appears to be about ten years old. “When it gets dark,” I say. “By the way: it's a telescope.” “When does it get dark?” “Where was Moses when the lights went out?” “Huh?” The boy's response--a symptom of a rapidly fading cultural memory--reminds me of something that happened to me earlier today: a kind of Rip Van Winkle Moment. It hit me while I was at the mall, shopping for a birthday gift for my wife. I was standing near a railing, taking a breather, when I developed the unnerving sensation that I had somehow strayed into the future. The crowded shoppers, shuffling all around me, appeared to be of a species not quite human. When I got home, my wife must have seen the shock in my face. She asked me was I alright, and I started to cry. I'm afraid I worried her a bit (it put a scare in me, too). She suggested that I scan the heavens tonight. I agreed. The conditions are optimal for viewing: there is no moon, and Saturn's rings are at a favorable tilt. I fix the telescope on Saturn. “Here you go,” I say to the boy. “Take a look at that.” “I don't see nothing,” the boy says. “Anything. You don't see anything.” “I don't talk like that. That's the old-fashion way of talking.” I realign the telescope. “You bumped the telescope,” I say. “On a telescope, a quarter of an inch can equal millions of miles.” “Huh?” “You have to be careful. Here: try again.” The boy fits his left eye to the eye-piece. “Cool,” he says, with a trendy inflection. “It is something,” I say. “How come it's in black and white?” “There's color. But it's very subtle. You're probably used to seeing color-enhanced photographs of the planets.” “Can you get it in color?” My wife has put on a recording of Paul Hindemith's Die Harmonie der Welt (The Music of the Spheres). I can hear it clearly through the window she left open for my benefit. We own a wide range of recorded music--from Gregorian Chant to Spike Jones. My wife has an uncanny talent for choosing music appropriate to a current situation, or for something about to happen. A few weeks ago she had an urge to listen to Luis Armstrong performing with The Hot Five. Moments after she'd started the music, an aggressive knock pounded our door exactly five times. I opened the door to a man wearing one of those Dr. Seuss-inspired, red and white stovepipe hats. He had a look of stunned defiance, like someone who had just been tossed out of a moving boxcar. “We painted your address on the curb,” the man said curtly. “We'd like a donation of fifteen dollars.” “Who asked you to paint our curb?” “You can make it ten, if you want.” “Who asked you to paint our curb?” He held up a clipboard. “It's for poor children.” “Which poor children?” He scowled at me, I closed the door, and a gentle soul from the 1920s began scatting--in lieu of the lyrics he'd forgotten--a verse of “Heebie Jeebies.” “If you concentrate to the right of Saturn,” I say to the boy, “you'll see its largest moon: Titan.” After a few seconds, the boy turns his face toward me. “I don't see nothing,” he says. His freckled face and double negatives remind me of Tom Sawyer--if Tom had worn a diamond earring stud. My thoughts shift, habitually, to the old chestnut about Mark Twain entering the world in tandem with Halley's Comet, and his prophetic musing that he would stick around until the comet made a return visit. I consider the fact that I was born the same year the first H-bomb was detonated, and am troubled by the parallel. “Titan won't look as big and bright as Saturn,” I say. “It's just a small speck, off to the side. It is there; believe me. But you can't see it by looking at it directly: you must see it by thinking about it, concentrating on its location. That's called 'averted vision'.” “Huh?” “Keep trying,” I say. “It's worth the effort. Titan is a mysterious world. It's the only moon in our solar system that has its own atmosphere. Scientists believe that it has oceans and lakes of hydrocarbons.” When I was a boy, Venus was believed to be an Edenic world: teeming with lush vegetation and exotic life-forms--shrouded by a canopy of water-vapor clouds. Our moon was yet unscarred by human footprints, and Pluto, still a legitimate planet, was a relatively new addition to the family. “Can we look at something else?” the boy says. “Sure,” I say. “How about the Ring Nebula?” “Cool.” “Do you know what that is?” “No.” “Well, I'm not too sure myself, actually. But I do know that it's a shell of expanding gas from a star that's getting ready to give up the ghost. Stars die like everything else, you know. But there's always something left over.” The boy yawns. “Let's have a look at that old Ring Nebula,” I say. I rotate northward the telescope's light-gathering business-end, center on Vega, and give a minuscule tap down to Lyra. I adjust the focus until a wispy O appears, then motion for the boy to take the helm. “I don't see--” “Don't say it,” I interrupt. “Let me check.” The music stops. “Okay,” I say. “There it is. It looks like a little Cheerio. Just stick with it. And don't bump the scope.” “Oh yeah,” the boy says. “It looks fuzzy.” “Good. That's a good description. Nebula means cloudlike.” “Fuz-zy,” the boy repeats, like Karloff's Frankenstein. “Do you realize that you are looking back in time?” I say. “Huh?” “A telescope is a time machine.” “For reals?” “In a manner of speaking: yes. The light from the Ring Nebula takes more than two thousand years to reach us, traveling an enormous distance through time and space. When you look at the Ring Nebula, you are literally looking back in time. What you see may no longer even be there. Think about that.” “Can we look at something else?” the boy says. “Just wait a minute. Let's try to understand the smallest part of this mystery. I want you to get a grasp on what we're dealing with here.” “Then can we look at something else?” “Think,” I say. “Think about time; about all the things that have been, that are, that will be. Because two thousand...three thousand...a million years is a mere drop in the bucket--from a cosmic perspective.” The boy reaches for the focusing knob. “Don't touch that,” I say. “For starters, let's contemplate your age. How old are you?” He appears to be stumped. “When's your birthday?” “November twenty-four.” “In what year were you born?” Blank. “What grade are you in?” “Fifth.” “Alright. So you're probably ten--or thereabouts. You have traveled through time for at least ten years.” Decades seemed to me profound increments when I was the boy's age. I had imagined the passage between decades as measured steps through gigantic gates: flanked by mute and faceless sentries, clad in antique armor, and wielding ferocious-looking pikes. I also considered it preordained that my first two-digit birthday aligned closely with the procession from 1959 to 1960 (the O in 1960 comforted me with its link to my birth year, natural strength of design, and ease of divisibility). 1959, of course, had its distinctions. New stars completed the symmetry of our flag, and the Lincoln Memorial appeared suddenly on the backs of pennies. Additional stars in an already crowded field of stars were barely noticeable, but an altered penny was something that could not be ignored. I remember staring deeply into the image of the memorial, past the twelve columns, to the dim suggestion of a seated Lincoln, looming like an unformed thought in the back of my mind. The head's side remained unchanged: Lincoln's profile, peering stoically into the future. “When did you first became aware of the passage of time?” I say to the boy. His eyes are scary: I cannot tell what--or if--he is thinking. I look deeply into his abnormally large pupils, and perceive the afterglow from a billion video games. “Huh?” He plunks his favorite dull string. “See this?” I say with growing agitation, wagging my finger at the telescope, as if scolding it. “Galileo was the first person to use a telescope to study the heavens. That was . . . over four hundred years ago. You've heard of Galileo, haven't you? Doesn't matter.” I walk counterclockwise around the telescope, like a baseball pitcher trying to regain his rhythm. My wife has selected music from the sixteenth century: alloys of math and metaphysics. “Did you know,” I say to the boy, “that right here, right where we are standing, there was once an ancient sea, thriving with prehistoric animals: the likes of which no longer exist on our planet? But the light that shone on those creatures is still shining somewhere out there.” I trace the Celestial Equator with a swoop of my right hand. “In other words: the past, the present, and the future weave to form one fabric. That fabric is called Eternity.” The boy studies my face. “Can you see aliens with your microscope?” My wife increases the volume on the music. A Kyrie.

©2011 by Timothy Reilly

: During the 1970s, Timothy Reilly was a professional tuba player in both the United States and Europe (in the latter, he was a member of the orchestra of the Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy). He is currently a substitute elementary teacher, living in Southern California with his wife, Jo-Anne Cappeluti: a published poet and scholar, who also teaches university English courses. His short stories have been published in The Seattle Review, Blue Lake Review, Slow Trains Literary Journal, Amarillo Bay, Foliate Oak Literary Review, Passager, and several other print and online journals.

|

| Home | Contributors | Past Issues | Search | Links | Guidelines | About Us |

|

.

|